“What Is An Aortic Valve Gradient?” Asks Jack

Written By: Adam Pick, Patient Advocate, Author & Website Founder

Page Last Updated: June 6, 2025

At 64, Jack has recently been diagnosed with severe aortic valve stenosis. Jack writes, “Adam – I’m like a deer in headlights right now. I need aortic replacement soon. I’m curious, the doc mentioned an aortic valve gradient following my echocardiogram. What the heck does that mean? Thanks for all you do, Jack.”

Jack asks a good question about aortic valve gradients (also known as AVG). In fact, I have never received a question about aortic valve gradients, so I just spent some time researching this diagnostic measure for valvular stenosis.

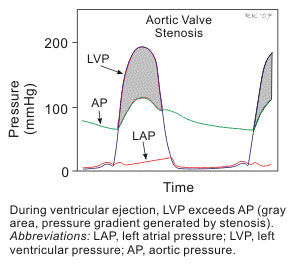

According Cardiovascular Physiology, stenosis of the aortic valve leads to a pressure gradient across the valve during the time in which blood flows through the valve opening. This aortic valve gradient is expressed as an increase and decrease on each side of the defective valve. The magnitude of the pressure gradient depends on the severity of the stenosis and the flow rate across the valve.

Aortic stenosis is characterized by the left ventricular pressure being much greater than aortic pressure during left ventricular ejection (see the shaded gray in figure above). Normally, the pressure gradient across the aortic valve is very small (a few mmHg); however, the pressure gradient can become quite high during severe stenosis (>100 mmHg). The aortic valve gradient results from both increased resistance (related to narrowing of the valve opening) and turbulence distal to the valve.

If that was too scientific for you, here is my layman’s interpretation… In patients with aortic stenosis, the left ventricle has to “work overtime” to compensate for the constricted blood flow through the valve. The aortic valve gradient increases as a result. Over time, this can severely damage the patient’s left ventricle as it thickens and dilates. This is exactly why I needed an aortic valve replacement operation.

According to cardiologist, Dr. Robert Matthews, heart catheterization can also be used to judge severity of the valve stenosis (if undeterminable non-invasively) by recording the aortic valve gradient across the valve, estimating the stenotic area , evaluating the left ventricular function and to determine if coronary artery disease is concurrently present.

Related Links:

I hope this helps explain more about the gradient of the aortic valve.

Keep on tickin!

Adam

|

James (Jim) Rohan says on July 20th, 2010 at 11:30 am |

|

One year ago I had my aortic valve replaced and last week my doctor performed an echocardiogram. I received a call from the doctor’s office giving me the results and it was for that the replacement valve was gradient. I have a followup appointment in September, but after doing some research believe that the replacement valve having this situation might be cause for another surgery to replace the replacement. Could you give me some additional data on how common this situation is and am I correct in assuming I am heading for another open heart surgery? Thanks |

|

|

Douglas I. Pereira says on September 15th, 2010 at 1:10 am |

|

Jim, All mechanical valves have a gradient that is intrinsic to their design (friction, that metal and plastic is heavier than normal valve tissue, etc.), and manufacturers do their best to keep it as low as possible. The gradient of a mechanical aortic valve is usually around 8 to 22 mmHg, which is near the gradient of a normally functioning (albeit mildly stenotic) natural valve. Also, newer mechanical aortic valves have lower gradients, due to improvements in technology, so ask your cardiac surgeon to use the newest model available if they recommend a mechanical valve. If you have serious health conditions (i.e. COPD, diabetes, renal disease), anticoagulation is contraindicated, or you are elderly, and you have “poor inotropic reserve” (i.e. the aortic valve gradient fails to rise at least 20% when dobutamine is infused, which means your left ventricle has failed from the strain), your cardiac surgeon will likely recommend a biological valve, which has no gradient, doesn’t require lifelong anticoagulation (which has huge risks), but will eventually become stenotic after around a decade or two, and require replacement (but technology is improving, and valve lifetimes are being extended every day). So it’s a trade-off between re-operation and the risks of anticoagulation, and only you and your cardiac surgeon can make that decision as to what’s best for your situation. |

|

|

Marie Gabriel says on February 8th, 2011 at 3:23 pm |

|

I am female 70 years old, no high blood pressure or diabetes, I am 5 ft 2 inches and weigh 115 lbs. I have aortic value stenosis classified as severe. I have been working out a a gym until recently, (doc suggested I stop) but have no symptoms of angina, dizziness, chest pain or shortness of breath. |

|

|

Randy Brown says on December 1st, 2012 at 10:03 am |

|

In 2008 I had a Acending Arotic anyuruem and 2.77 valve (tissuie) The did a graft into the root but did nto take out teh root due to how larege I was I was born with Biecuspis I have soft tissuie on right side 11mm last year 9.5mm and a Graduit of 17 accross A-valve What are you thoughts |

|

|

Chris DeBano says on May 16th, 2013 at 1:04 pm |

|

Thanks for your understandable explanation of gradients. I had re-do aortic valve surgery last year and because of scar tissue,they had to replace my 24mm valve with a 19mm valve. They kept mentioning my gradient numbers and until I read your explanation, I didn’t know what the significance of that reading was. You’re providing a great service by bringing understanding to such an important, anxiety provoking subject. |

|

|

Gail says on June 17th, 2013 at 11:25 am |

|

I’m 46 and in 1996 had a “Pigs” valve to replace my aortic valve – since then (in 2007) for my 40th present I had a metal valve installed. I have annual checks and was advised that my gradient was 22 – can you please confirm what this means? If my gradient goes above this does this mean a third valve replacement? |

|