Heart Surgery: Past, Present & Future

By Adam Pick on December 21, 2017

Ready to go on a wonderful journey through the evolution of heart surgery?

In this video… Dr. Paul Fedak, the Professor of the Department of Cardiac Sciences at the University of Calgary, describes the pioneers and the medical breakthroughs that transformed heart surgery from taboo to mainstream medicine. The video is 17 minutes long… And, worth every second of it.

Keep on tickin’ Dr. Fedak!

Adam

P.S. For the hearing impaired members of our community, I have provided a written transcript of the video below.

I want you to imagine that you’re just about to undergo major open-heart surgery, and they’re putting you to sleep and you’re not sure if you’re ever going to wake up again. When you look up, your surgeon is standing and it looks like he’s praying. Well a famous surgeon once said that every surgeon carries within himself a small cemetery, where, from time to time, he goes to pray. Those are some pretty haunting words.

Those words really get at this paradox, this contradiction of surgery. To do surgery, you have to hurt somebody in order to heal them and there’s a cost; there’s a heavy, heavy burden. Heart surgery was the final surgical frontier. Every other organ system had been operated on and conquered, but not the heart. Why is that? The heart was a forbidden zone. In fact, there is a famous surgeon who once said at the turn of the century that anyone who attempts to operate on the human heart would lose the esteem of his colleagues. For doctors that’s a big deal.

Why is a forbidden zone? Well, one reason is that we didn’t have the techniques necessary to operate on this vital organ. There were not techniques in surgery that would allow for something like that. Also, there is this cultural significance of the heart. It was a forbidden zone because the heart is life. In every culture from the beginning of mankind, we’ve understood that a beating heart is life. When the heart stops beating, it’s death. In fact that was the medical definition of death for a very long time, if your heart stops beating. Every TV show you watch, what do you do if you think someone is dead? You feel for their pulse. No pulse, you’re dead! To do open-heart surgery, we have to stop your heart – it’s death.

To train heart surgery is long and it’s difficult. It takes at least ten years of long days and sleepless nights, to have the privilege of doing this. There was a surgeon that once said that the toughest thing about heart surgery is getting the chance to do it. It’s a very elite area of surgery. We take one person a year here in Calgary to train in heart surgery, and there are only about eight spots across the entire country, to train in heart surgery. There’s maybe 100 active cardiac surgeons in the entire country, so it’s pretty elite.

What’s it like to do heart surgery? What does it take to do heart surgery? Well, I like to say you have to be an NFL quarterback, a chess master, and an air traffic controller all at the same time. You have to coordinate a whole team and you’ve got to do things right.

What’s it like to actually do a heart surgery? Well the first thing to do heart surgery is you have to get there. We have to cut you. We have to cut right through the core. We have to cut through your breast bone. We have to take a saw and cut that bone in half. Then we’re not quite there yet. There is a sac around your heart and the heart sits within that sac. We have to cut through that sac to get to the heart. When you do, it’s incredible. When you hold that beating human heart in your hands, it’s the ultimate thrill. It’s such an incredible organ. It’s so filled with life. The colors, the impact of this heart is incredible. It’s got such a will; it just wants to keep going. We say that; we say people have heart. I can see that when I do surgery, when I hold that heart.

To do heart surgery, you have to stop the heart from beating. We have to put a clamp on the heart; we cut off its blood supply. When you put that clamp on, the heart slowly starts to deflate and it slowly stops beating and you see a flat line on the monitor. At that moment, you know you’re standing at the gates of that small cemetery. The burden of what you’re doing is quite intense. The room stops for a second. Sometimes I think this is the worst job in the world – why would I take on this burden?

Then at the same time, this is, again, a contradiction is it’s also the ultimate trust. Someone has given me their trust to do this, which is also something very extraordinary. When I speak to patients and I talk to them about all the risks and benefits of surgery and what we’re going to do, I spend about half an hour telling them all these technical details and they’re looking at me. I know they’re not really hearing anything I’m saying. They’re looking deep at me and they’re just saying to themselves do I trust this guy. They do. They give me this opportunity and I wonder how does an ordinary guy like me get to have that kind of trust and that responsibility? It’s truly extraordinary.

That level of trust is really interesting. There’s something about cardiac surgeons and heart surgeons, they come in all shapes and sizes, ethnicities, men, women with different personalities. There’s something that’s common about all of them. I’ve had an opportunity to train with and work with heart surgeons around the world and I think it’s this. I think it’s kaizen. Kaizen is a Japanese principle of continual self-improvement. It’s always trying to learn from what you’ve done and get better and better. I think that’s the one thing that all heart surgeons have. They have to have that because to take on that burden and that responsibility, to have that level of trust, you need to learn from everything that you do.

As heart surgeons, we have to be perfect, but you can’t be perfect. We chase perfection and in the chase for perfection, we catch excellence. Excellence is what we do. Ninety nine times out of 100 we can do open heart surgery now, safely, effectively. You live longer. You feel better. That’s remarkable because it wasn’t that long ago that heart surgery was impossible.

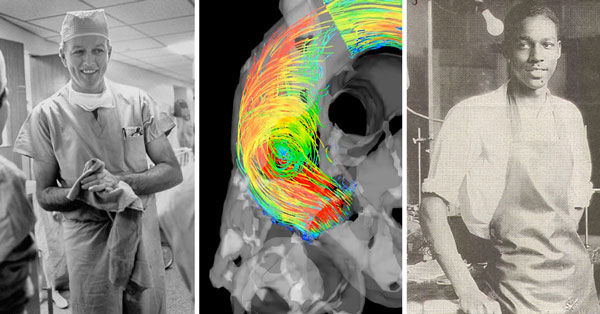

This picture is really special to me. It’s November 1944, Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. This is the first blue-baby operation. Babies were being born with a heart defect and they were blue because there was no enough of the oxygenated blood; the pink-red blood was mixing with the blue blood through this defect in their heart. There was no cure for it. There were no treatments. You could give them medicine but they would die. There was no hope for these little babies.

Well there’s a surgeon and his name was Alfred Blalock. He was experimenting in his research laboratory for many years on a way to improve the circulation. He came up with some special techniques to do, to create a shunt in the heart and he applied this. This is the first operation. This is Blalock right there. He’s standing and his hands are deep in this baby’s chest.

Standing right across from him is a tall intern called Denton Cooley. It was his first week, and he was given this extraordinary opportunity to participate in this very first surgery. What’s incredible is Denton Cooley describes in his memoirs that when they took the clamp off the heart and allowed it to start beating again, they watched this blue baby slowly turn pink. They knew for the first time, he said, this was the dawn was heart surgery. It was possible. They knew it was possible.

Well that intern, this is him 50 years later, and that’s me standing right beside him. What an extraordinary opportunity I had to go to Texas and learn from this man. It shows you how – we’re one degree of separation. I’m one degree of separation from the dawn of heart surgery. That’s how short, how compressed the timeframe is in this specialty. It’s pretty incredible.

After I finished my training in Toronto and Chicago, I had this extraordinary opportunity to come to Calgary. I wanted to create my own program. I wanted to do heart surgery and also try to advance heart surgery. I was so inspired by the history of heart surgery, and I knew that I wanted to add maybe a chapter to the story of heart surgery. If not a chapter, how about a paragraph, even a sentence, something.

I was given this unique opportunity here in Calgary. This is the blueprint of the lab that I designed. That’s right next door. This building was an empty shell ten years ago when I came, and I was able to plan out exactly what I wanted. That’s an ordinary blueprint of a lab. There’s really nothing special about that. Sometimes you can take the most ordinary thing and make it extraordinary, simply by doing it with the right people.

That’s what we’ve been able to do in my research program. We’ve recruited and retained some of the top students and research associates and collaborators. We’ve instilled a culture of mentorship amongst all of us that’s been extremely effective, and I want to tell you about some of that work that we’re doing.

People are born with heart defects and abnormal heart valves. There’s bicuspid valve, where you’re born with a two flat valves instead of three. One thing we understand, if you think about a tap, you turn a tap on, the flow comes out in a very organized way. Well even if you put your finger over that tap just a tiny little bit, you get chaotic flow; you get a lot of abnormal flow patterns. Well that can cause trouble in the heart.

If you think of the Grand Canyon or something like that, over time abnormal blood patterns can cause real structural problems. We’ve never really had a way to see that abnormal flow patterns; we’ve never had a way to visualize them. Well now we do. We’re using the most advanced imaging technology; this is called 4D Flow MRI. For the first time, we can see deep within a patient’s chest and map out, in real space and time, these flow patterns. This is where the precision medicine comes in.

Heart surgery has come a long, long way. We’re now passed trying to get patients through a surgery. Now we know we can do the surgery really well. The technical parts of surgery are not that difficult. What’s really interesting is now the challenge is who to operate on and when to operate on them. This type of technology is going to tell us which of these patients we should operate on when and maybe when we shouldn’t operate on them, and that’s really critical.

Another thing that’s really interesting is that we’ve really focused on trying to get patients through the surgery, trying to survive patients through heart surgery. Now we can work on some of the finer details. One of the things that bother patients the most is going through the breast bone. Can you imagine that the way we close the breast bone is the same way they did it in 1944. You take stainless steel wire and you wrap it around the bone and you twist-tie it like a garbage bag. You hold it together until the bone heals, like any broken bone.

That really slows people down. They don’t like that. It’s painful and it limits their mobility. They’re not too happy about it. We thought, well, maybe we could still do an ordinary access to the heart but close it an extraordinary way. We use a special super glue to do that. We are the first group in the world to do this. We took it all the way from concept to clinical trial and it’s been really exciting to watch this evolve. People have adopted this technique and it’s still being adopted and the patients really love it.

One of the things that you’re most concerned about is heart attacks, and you should be because it’s the number one killer. Heart attacks are really – you develop blockages in the arteries on your heart and your heart muscle needs a lot of oxygenated blood. It’s always pumping and it’s always working. When those blockages get severe enough, you can cause a heart attack. If the blood supply is cut off to an area of muscle for long enough, that area starts to die.

Interestingly, it won’t ever recover. Once the heart muscle dies, we can’t fix it. We can do a lot of things but we can’t fix dead heart muscle. One of the greatest successes in heart surgery has been bypass surgery. We can go in as surgeons and we can create bypasses. We can go around those blockages; we create new blood vessels and it’s pretty incredible. We take arteries or veins from other parts of your body and we surgically put those on to the arteries. They’re only about a millimeter or two millimeters in diameter and we make blood flow through them around the blockage and restore blood flow.

That’s a great technique. It’s saved many lives and it’s very effective, but it’s not as effective if you’ve already had a heart attack. We see a lot of patients who come in and they have a heart attack and we have to do this surgery. It’s helpful, but it doesn’t fix the dead muscle. Whenever I operate on these patients, I look at that area and I think, well it’s right there in front of me and I can’t do anything about it. This is a whole new frontier.

Maybe there is something we can do. There are things called biomaterials. Biomaterials are actually biologic tissue, where the cells have been removed and what’s left is the scaffolding that holds all the cells together. We once believed that the scaffolding was just the passive material; now we know that it’s rich with signaling factors and growth factors that tell cells what to do. Tell cells to live or die, grow, regenerate.

We had access to some that came from an intestinal tissue, and some tissues are more regenerative than others. We thought, well what if we take this and intestinal tissue – the heart is not very regenerative, well what if we took this intestinal scaffolding and sewed it on the surface of the heart at the time of bypass surgery. Could we then target the heart muscle and restore its function, regenerate it.

Well we took that all the way from concept to the first human clinical trial in the world right here in Calgary. This is a picture of one of those patches on a human heart beside one of the bypasses I created. Standing across from me in that picture is Holly. Holly was my intern. She trained in my laboratory and she did a PhD on this project, and this was the very first one.

Well how does it work? We spent years in the lab trying to figure this out. How could this be of any benefit at all? What’s interesting is that when you have a heart attack, the cells in your heart, they’re scar-producing cells and they’re told to make more and more scar. You don’t want scar; you want muscle. In other words, the soil – there’s something wrong with the soil. We’re growing weeds in the soil and we need to grow flowers.

How do we change the soil? Well this biomaterial can do that. What we’ve done is we’ve done studies where we’ve interacted human heart cells with this biomaterial and it changes those cells. They don’t produce scarring anymore; they actually produce new blood vessels, tiny, microscopic blood vessels. I as a surgeon can go in and create big blood vessels, which is good but we also need those little micro vessels in that area of damage. When you hook those together, it’s incredible. You see an area where red is dead by MRI; this is some of our experiments. Six weeks later, we restored function. These were hearts that were defined as non-viable, meaning they’re dead; they’re not coming back. The heart does have reparative signals; we need to amplify them. We need to help it along and this maybe a very simple way to do it.

Holly presented this work at the American Art Association meeting, which is one of the largest medical meetings in the world. She won the Vivien Thomas Young Investigator Award. That was very special to me, that I was able to provide an environment for Holly to be so successful. It was very special to me as well because 14 years earlier, I won that same award when I was at the same stage of my training. It was also very special because of the name, Vivien Thomas. It wasn’t the Denton Cooley Award, that tall guy standing across the table. It wasn’t the Blalock Award. It wasn’t named after any heart surgeon actually.

Who was Vivien Thomas? Well, let’s go back to the Baltimore, that first blue-baby operation. There’s somebody standing behind the surgeon. He’s actually not wearing any gloves. He’s not really in the picture but he’s in the picture. Well that’s Vivien Thomas. Vivien Thomas was at every blue-baby operation and he was whispering in Blalock’s ear, the surgeon, a little to the left, a little to the right. He was actually instructing him how to do it.

Vivien Thomas was the laboratory technician of Blalock. He actually came up with the techniques that allowed the first blue-baby operation. He’s an African-American man at a time when not only would – he wouldn’t be treated extraordinary; he wouldn’t even be treated ordinary. He’d be treated less than ordinary. An African-American man at that time was allowed to be a janitor in the hospital, and here he was, pioneering open-heart surgery. He actually was a college dropout, never had a degree, but he was given an honorary doctorate from Johns Hopkins for his work and he’s widely recognized. That’s why that award is so very special.

When I look at this picture, to me it means a lot because these three men, at this single moment in time, represent the three pillars of academic medicine: research, education, and patient care. When you take transformative research and compassionate, bold patient care and inspired mentored education, and you nurture that like we do here in the medical school – that’s why we have a medical school, for this reason – and when you take those things together, when those three things blossom, you truly have something very extraordinary. That’s the extraordinary story of ordinary heart surgery.

Thank you!

|

rubart says on December 21st, 2017 at 3:07 pm |

|

I was already in awe of the miracle my wonderful surgeon and his equally wonderful team performed on me. But after watching this video, I’m in super-awe of the people who pursue this work. And I’m so thankful that they do. Just as with the rest of the people on this site, I owe them my life. I’ve decided that the best way to express my gratitude is to spend the additional years they gave me doing as many good deeds for others, in whatever ways I can, for as long as I can. So that my surgeon and team might one day say, “We’re happy to save every life we can–but we’re especially happy that we saved this one.” P.S. to Adam — Congrats on your 12th anniversary. And many more to come! |

|

|

Bobby Stolp says on December 28th, 2017 at 8:45 am |

|

I love the respect and due that Dr. Fedak gave to Vivian Thomas. I would encourage anyone interested in the subject to read Mr. Thomas’ memoirs. Thanks for translating it Adam. Happy Heartbeats all! |

|

|

Michael Zernell says on January 16th, 2018 at 11:18 am |

|

Adam, I have a question for you. I was born with the Bicuspid Aortic Valve, I have and always had a murmur. I started seeing a Cardiologist about 10 years ago. On the 27th of Oct 2017 I had a vicious Migraine that sent me to the ER. It turned out that it was Sepsis that settled into my Heart and now it is Epicondylitis. I self referred to Cleveland Clinic Just before Christmas and got a call on the 11th of January 2018. They have me scheduled for Surgery on the 23rd of January 2018. I was told that the epicondylitis is on my artic and mitral valves and they are about 1 cm sq in size, I have mild to moderate stenosis and mild to moderate regurge on the aortic valve. My question is Why has this turned so urgent? Is Cleveland known for the quick turn-around? Thanks, Mike |

|

|

Jolanda Slagmolen-Flores says on February 6th, 2018 at 12:38 am |

|

Dr. Fedak will be performing a heart valve replacement and aortic aneurysm repair on me in the next couple of months. I loved this presentation – it really gave me an insight into the kind of person he is and put me much more at ease with respect to the surgery 🙂 |

|