Bioprosthetic Versus Mechanical: Which Valve is Right For You?

Written By: Allison DeMajistre, BSN, RN, CCRN

Medical Expert: Marc Gillinov, MD, Chair of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Cleveland Clinic

Reviewed By: Adam Pick, Patient Advocate

Page Last Updated: May 29, 2025

Patients with a significant heart valve defect (e.g. aortic stenosis) are often not candidates for a heart valve repair procedure. Instead, they will need to have the diseased valve replaced. A valve replacement procedure requires some decision-making since there are different options. First, there are bioprosthetic valves, including pig and cow valve replacements. Alternatively, there are mechanical valves made from titanium and carbon materials.

Bioprosthetic and mechanical valves have critical differences and distinct advantages and disadvantages. Every patient should know and understand all the facts before deciding which type of valve to use for a replacement since it will be part of them for many years, and sometimes, for the rest of their life.

Dr. Marc Gillinov, Chair at the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery at the Cleveland Clinic, weighed in to provide insight into valve replacement options and what patients need to consider when making that important choice.

Key Learnings About Heart Valve Replacements

Dr. Gillinov shared several vital insights in this video. Here are the key takeaways for patients to consider when learning about heart valve replacement options:

Cardiothoracic Surgery at Cleveland Clinic

Repair versus replacement

- Surgeons at the Cleveland Clinic perform over 2,000 heart valve operations each year. Before every surgery, the doctor and patient discuss the type of heart valve surgery and whether it will be a valve repair or a replacement. “In almost all cases of mitral valve prolapse, which causes a leaky valve, we can repair the valve,” Dr. Gillinov said. “In contrast, when patients have aortic valve stenosis, meaning the valve is narrowed, that would be replaced.” Dr. Gillinov stressed that surgeons always discuss a valve replacement, even if the original plan is to repair a valve. “Occasionally, we find a valve that we thought we could repair, but there is so much damage that we have to replace it. In every heart valve procedure, a discussion of valve replacement is absolutely necessary.”

- After discussing the possibility that plans may change and a repair procedure may turn into a replacement procedure, Dr. Gillinov believes the following question to be answered is, “What kind of valve do I want?” There are two types of valve replacements: mechanical valves and bioprosthetic valves. “Some people call mechanical valves metal valves,” said Dr. Gillinov. “They’re actually made out of carbon more than metal, but they do have some metal in them.”

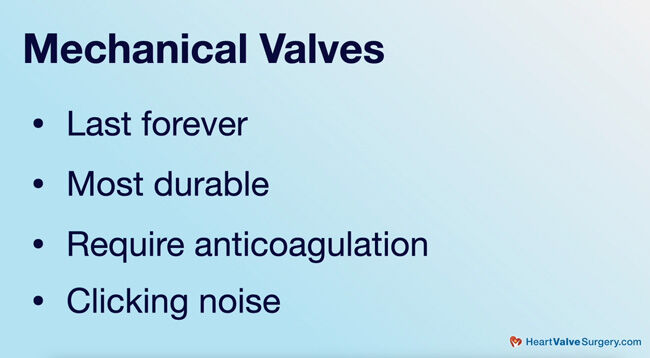

Mechanical valve facts and features

- When considering a mechanical or bioprosthetic valve, Dr. Gillinov said, “I think the most important point to know is that they are both very good, but there are key differences. Mechanical valves usually last forever. They almost never wear out, and it is uncommon for someone with a mechanical valve to need a reoperation ever in his or her life.”

- Unfortunately, Dr. Gillinov points out, mechanical valves “come with some baggage.” Even though mechanical valves are durable, their ” baggage ” includes anticoagulation or blood thinners. “That anticoagulant has to be Coumadin, which is also called warfarin. The reason why mechanical valves require an anticoagulant is that they tend to cause blood to clot on the surfaces or discs of the valve,” said Dr. Gillinov.

- Gillinov points to three essential issues patients must know when choosing a mechanical valve. The first is that an anticoagulant thins the blood, putting a patient at greater risk for bleeding. Next, when a patient is on Coumadin, it requires a monthly blood test to check that the medication level in the blood is within range. And finally, mechanical valves make a slight clicking noise. “It’s not loud, but almost anyone who has a mechanical valve inside their heart can sense or hear this small click it makes every time it closes.”

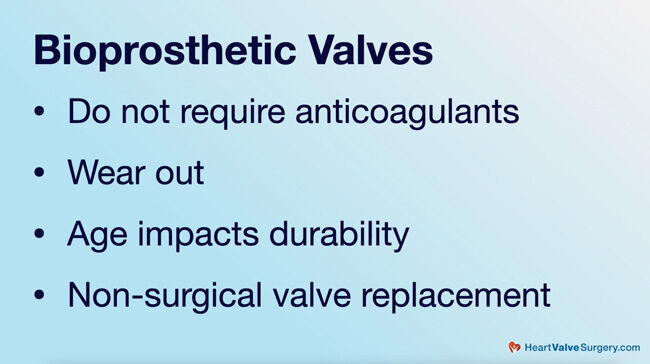

Bioprosthetic valve facts and features

- Bioprosthetic, also called biological valves, come from pigs or cows. “The pig valves are actually pig aortic valves, which are mounted on a sewing ring or circular ring,” Dr. Gillinov said. “The ring has the valve in the middle; we sew that ring into the heart.”

- The cow, or bovine valves, are made from the lining of the cow’s heart, called the pericardium. “The lining, which is leather-like material, is fashioned into a valve. Both kinds of valves work very well, and there is little difference between them, “ said Dr. Gillinov.

- Two main features of the bioprosthetic valves differ from the mechanical valves. First, bioprosthetic valves don’t require blood thinners. “However, the pig and cow valves can wear out,” Dr. Gillinov points out. “They almost always last at least ten years; we’ve seen as long as 22 years. It’s uncommon for them to wear out in five or six years.”

- Interestingly, the older the patient, the longer the bioprosthetic valves last. “If you’re 65, and you get a cow or pig valve, there’s a very good chance it will last your whole life,” Dr. Gillinov told us. “Some people in their 50s will choose a pig or a cow valve because they don’t want to be on blood thinners. That means when these people get into their 60s, they will likely need a new valve.” However, Dr. Gillinov points out they may not need surgery to replace the worn-out valve. “There’s a good chance we can take a new valve, crimp it, or fold it like an umbrella, thread it up a vein or artery from your leg, and deploy it in the housing of the old pig or cow valve because the old valve gives a perfectly circular landing zone such that we can put a new valve inside.” He said there’s no guarantee a 50 or 60-year-old patient won’t need surgery if they choose a bioprosthetic valve, but there is a good chance they won’t.

Which valve should you choose?

- Gillinov believes that both valves are very good. “The blood flow through a mechanical valve is a little superior to that of a biological valve, but it’s generally not significant,” he said. One study from California from the New England Journal of Medicine published data that people in their 40s and 50s may live longer when they have a mechanical valve replacement instead of a biological valve. But Dr. Gillinov said, “People should choose the valve based on their lifestyle, wishes and needs. If you are 55 years old and your favorite activity is bicycle riding, and you ride in races, and you are often knocked off your bike, essentially you get beaten up and bruised, and you don’t want to be on a blood thinner, a biological valve might be best for you. If you’re 70 years old, you should almost certainly choose a biological valve because that valve is likely to last your whole life.”

- “The key point here is it’s a discussion,” Dr. Gillinov said. “ A discussion between you, your needs, and the surgeon and what he or she thinks might be best for you. At the end of the day, both of these types of valves, mechanical and bioprosthetic, are excellent choices.”

Thanks Dr. Gillinov and The Cleveland Clinic!

On behalf of our patient community, many thanks to Dr. Marc Gillinov for sharing his

knowledge and expert insight about the differences between mechanical and bioprosthetic valves and what patients need to know before deciding which one is right for them. Also, we want to thank The Cleveland Clinic for continuing to take great care of heart valve patients.

Related Links:

- See Dr. Gillinov’s Surgeon Profile and Patient Reviews

- Check out the Cleveland Clinic Heart Valve Microsite!

- Heart Valve Patients Celebrate Their Fixed Hearts, Dr. Gillinov & Our Community

Keep on tickin!

Adam

P.S. For the deaf and hard of hearing members of our community, I have provided a written transcript of this interview below.

Video Transcript:

Dr. Marc Gillinov: I’m Dr. Marc Gillinov, Chair of the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery at the Cleveland Clinic. Here at the Cleveland Clinic, we perform more than 2,000 heart valve operations every year. Before each operation, there’s a discussion with the patient, between the doctor and the patient, about the type of heart valve procedure we’re going to do. It begins with the discussion of repair of the valve versus replacement of the valve.

In almost all cases of mitral valve prolapse, which causes leaking valve, we can repair the valve. Mitral valve prolapse, we can usually repair. In contrast, when patients have aortic valve stenosis, meaning the valve is narrowed, that valve would be replaced. Even if we plan on repairing the valve, we always discuss back-up options. Occasionally, we find a valve that we thought we could repair, but there is so much damage that we have to replace it. In every heart valve procedure, a discussion of valve replacement is absolutely necessary.

The main point when discussing valve replacement is to answer the question, if I need a valve replacement, what kind of valve do I want? There are two kinds of valve replacements. We have mechanical valves, and we have bioprosthetic valves. Some people call mechanical valves metal valves. They’re actually made out of carbon more than metal, but they do have some metal in them.

Mechanical valves and bioprosthetic valves, or biological valves, are very different. I think the most important point to know is that they are both very good, but there are key differences. Mechanical valves usually last forever. Mechanical valves, these carbon-based valves are the most durable valve choice. They almost never wear out, and it is uncommon for someone with a mechanical valve to need a reoperation ever in his or her life. Mechanical valves are the most durable option that we have, but mechanical valves come with some baggage.

The most important thing about mechanical valves after durability is anticoagulation or blood thinners. If you get a mechanical valve, you have to take an anticoagulant or blood thinner. That anticoagulant has to be Coumadin, which is also called warfarin. The reason that mechanical valves require an anticoagulant is that they tend to cause blood to clot on the surfaces or discs of the valve. Therefore, you need a blood thinner.

The blood thinner has its own issues. First and foremost, if you are on an anticoagulant, and you are involved with a situation that causes bleeding, for example, major trauma, or a bleeding ulcer that won’t stop, being on an anticoagulant makes this a much bigger deal, harder to manage. In addition, if you are on Coumadin, this particular anticoagulant, you require monitoring, meaning you have to get a blood test once a month, or you can test at home with a little finger stick kit to make sure that you are in range. Mechanical valves, the most durable, require an anticoagulant. Finally, they do make a slight clicking noise. It’s not loud, but almost anyone who has a mechanical valve inside their heart can sense or hear this small click it makes every time it closes.

Now, the other type of valve replacement choice is a bioprosthetic valve, or a biological valve. These valves come from pigs or cows. The pig valves are actually valves. They are pig aortic valves, which are mounted or placed on a sewing ring, a circular ring. We sew that ring into the heart. The ring has the valve in the middle.

The cow valves, or bovine valves, were actually initially made out of pericardium, which is the lining of the cow’s heart. This lining, which is leather-like material, is fashioned into a valve. Both of these kinds of valves, pig valves and cow valves, work very well. There is little difference between them.

The main features of pig or cow valves, bioprosthetic valves, are first that they do not require anticoagulants. They do not require blood thinners in general. There’s some controversy, but in general, pig or cow valve, no blood thinners. However, the pig and cow valves can wear out. They almost always last at least 10 years, and we’ve seen as long as 22 years. It’s uncommon for them to wear out in five or six years.

If you get a pig or a cow valve, you should think, I ought to have ten years, maybe even more with this valve. It turns out that the older you are, the longer pig and cow valves last. If you’re 65, and you get a cow or a pig valve, there’s a very good chance it will last your whole life. These days, though, some people in their 50s will choose a pig or a cow valve because they don’t want to be on blood thinners. That means when these people get into their 60s, they will likely need a new valve. There is a reasonable chance that they won’t need surgery to get that new valve.

Specifically, let’s say you’re 65 years old. You come in with a worn-out pig valve. There’s a good chance that we can take a new valve, crimp it, or fold it like an umbrella, thread it up a vein or artery from your leg, and deploy it in the housing of the old pig or cow valve because the old pig or cow valve gives a perfectly circular landing zone such that we can put a new valve inside. No guarantee that you won’t ever need surgery again if you’re 50 or 60, and you get a pig or a cow valve, but there is a good chance.

Finally, if someone said, well, which valve is better? Which one works better? Which one would your heart prefer if your heart could talk? The answer is they are both very good. The blood flow through a mechanical valve is a little bit superior to that of a biological valve, meaning the mechanical valve allows a bit more blood flow, but it’s generally not significant.

There is some data that people in their 40s and 50s may live longer if they get a mechanical valve than a biological valve. That was from a big study from the state of California, published in the New England Journal of Medicine. However, people should choose the valve based upon their lifestyle and their wishes and needs.

If you are 55 years old, and your favorite activity is bicycle riding, and you ride in races, and you are often knocked off your bike, essentially you get beaten up and bruised, you don’t want to be on a blood thinner. A biological valve might be best for you. On the other hand, if you’re 70-years-old, you should almost certainly choose a biological valve because that valve is likely to last your whole life.

The key point here is it’s a discussion, a discussion between you, your needs considered, and the surgeon and what he or she thinks might be best for you. There are some instances where one valve will fit better than another. At the end of the day, both of these types of valves, mechanical valves, and bioprosthetic valves, are excellent choices.