Doctor Q&A: The Watchman, Atrial Fibrillation & Heart Valve Disease

Written By: Adam Pick, Patient Advocate & Author

Medical Expert: Dr. Marc Gerdisch, Chief of Cardiac Surgery at Franciscan Health

Published: September 11, 2023

We just received a great patient question from Lee about heart valve surgery, atrial fibrillation and the Watchman device. In his email, Lee asked, “I’ve had three aortic valve replacements and valve repair plus an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. All functions are good currently, but AFib persists 3.2% of the time. After oral surgery and a ruptured vein causing a hematoma, I had to defer Eliquis to control bleeding. My current cardiologist thinks I should consider the Watchman procedure as a safety measure. What have you heard about that procedure?”

To provide Lee an expert response, we interviewed Dr. Marc Gerdisch, the Chief of Cardiac Surgery at Franciscan Health in Indianapolis, Indiana. During his extraordinary career, Dr. Gerdisch has performed over 6,000 cardiac procedures and successfully treated more than 100 patients in our community.

Key Learnings About The Watchman, AFib and Heart Valve Disease

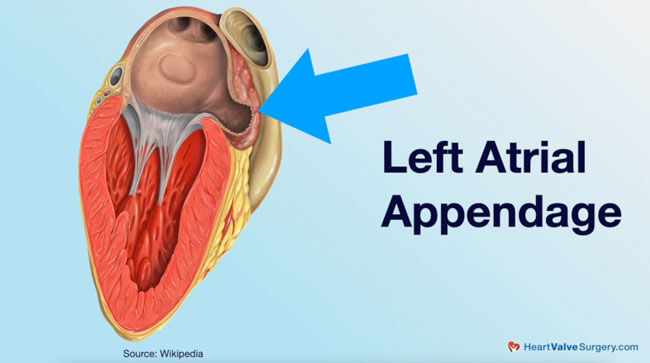

- While the left atrial appendage (LAA) performs select functions within the body (including the secretion of hormones), it is not critical to a patient’s survival. However, the LAA does put patients at risk for the development of blood clots which can lead to stroke.

- The Watchman is a medical device designed to close the left atrial appendage and therefore reduce the patient stroke risk. Dr. Gerdisch suggests that the Watchman is a good device. However, in clinical trials, the Watchman did not outperform the use of warfarin, known as the “gold standard” for preventing clot formation, for thromboembolic risk reduction.

- Determining patient risk for stroke can be measured using the CHADS-VASC score and help medical teams evaluate treatment options.

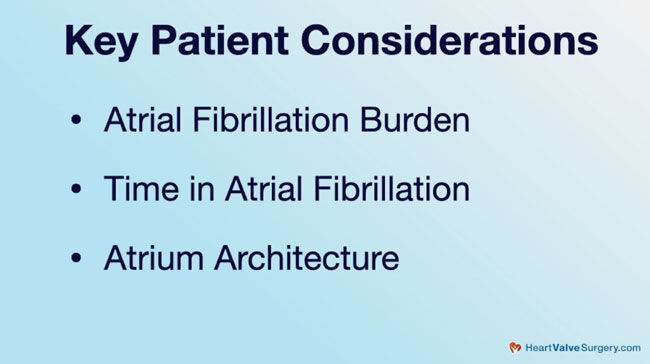

- The period of time in which a patient experiences atrial fibrillation is another indicator of whether-or-not treatment may be advantageous.

- For patients with heart valve disease and atrial fibrillation, it is critical that the patient’s medical team evaluate many additional factors to develop a long-term treatment plan that may consider appendage size, atrium architecture and comorbidities.

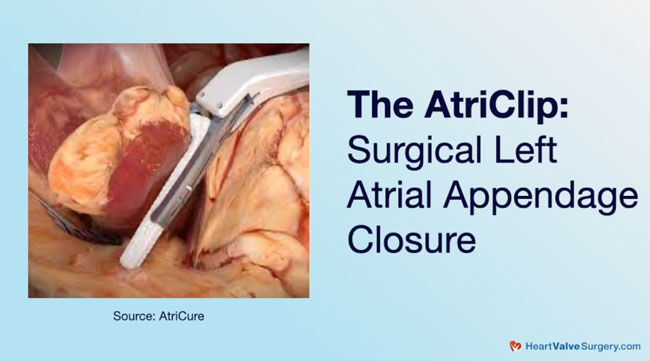

- The LeAPPS Clinical Trial is a new clinical trial designed to determine whether closing the left appendage prophylactically is appropriate using a clip which takes about 30 seconds during open heart surgery.

Many Thanks to Dr. Gerdisch & Franciscan Health!

On behalf of our entire patient community, many thanks to Dr. Gerdisch for sharing his clinical experiences and research with our community! Also, many thanks to the Franciscan Health team for taking such great care of heart valve patients.

Related links:

- Surgeon Insights: Minimally-Invasive Mitral Valve Repair Surgery

- Dr. Gerdisch Interview: The Different Faces of Mitral Valve Disease

- See 100+ Patient Reviews for Dr. Gerdisch

Keep on tickin!

Adam

P.S. For the deaf and hard of hearing members of our community, I have provided a written transcript of the video with Dr. Gerdisch below.

Video Transcript:

Adam Pick: Hi, everybody, it’s Adam with heartvalvesurgery.com, and today we’re answering your questions all about heart valve surgery, atrial fibrillation, and the Watchman Procedure. I am thrilled to be joined by Dr. Marc Gerdisch who’s the chief of cardiac surgery at Franciscan Health in Indianapolis, Indiana. During his extraordinary career, Dr. Gerdisch has performed over 4,000 heart valve repair and heart valve replacement operations. Dr. Gerdisch, it is great to see you again, and thanks for being with us today.

Dr. Gerdisch: Always a pleasure, Adam. Thanks for having me.

Adam Pick: Dr. Gerdisch, we are going to be answering a patient question, but first I want to take a quick minute and thank you and your team there at Franciscan Health for the incredible care you’ve provided to patients in our community. Now well over 100 of our patients have had successful heart valve surgery with you and your team, and I just want to say thanks so much for giving them another chance at life.

Dr. Gerdisch: Thanks, Adam. It’s really been our privilege. We love having that conduit of communication with folks through your site. Thank you.

Adam Pick: Yeah, and so Dr. Gerdisch, let’s get to Lee’s question, and it involves not one but two of your specialties being heart valve surgery and atrial fibrillation. Lee’s question is “I’ve had three aortic valve replacements and valve repair plus an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. All functions are good currently, but AFib persists 3.2% of the time. After oral surgery and a ruptured vein causing a hematoma, I had to defer Eliquis to control bleeding. My current cardiologist thinks I should consider the Watchman procedure as a safety measure. What have you heard about that procedure?”

Dr. Gerdisch: It’s such a great question because we could funnel right down to the Watchman, but it really encompasses a lot about historically what’s going on with management of the left atrial appendage, and it interweaves, of course, this element of atrial fibrillation, which he’s actually having later onset in a sense. He’s had a bunch of operations. He’s got a device in. The fact that he has a device is probably the reason he knows he has AFib. He may not be symptomatic for it, but because he’s monitored 24/7, they know what his heart rhythm is doing, and it’s 3.2% of the time, so in burden terms, in the terms of how much time the patient’s spending in AFib, it’s not a very big number.

Let’s back it up a little bit with respect to just indications, why manage an appendage? Why do anything to close the left atrial appendage, because that’s what a Watchman does. The Watchman closes the left atrial appendage, which is an outpouching. Think of it like a windsock hanging off the upper chamber. That windsock is – embryologically, it’s your left atrium. It makes up a lot of the left atrium hen you’re an embryo. As we continue from fetus to born human, our atrium at that point is actually constructed mostly of the same tissue as the pulmonary veins, so those are the veins that bring the blood back to the atrium from the lungs, and then we just have this remnant, this leftover part, basically, from our fetal development.

People say what does it do. We know that it does a few things, none of which are crucial to our survival, so one of the things it does is the left atrial appendage secretes a hormone. It’s a natriuretic peptide. It’s a peptide or a protein that helps eliminate fluid from your body, so we say you wouldn’t want to get rid of that appendage if it’s doing that for you, but the reality of it is that there are several other places in your body that secrete the same thing, and we know that when we eliminate the left atrial appendage that initially we see a decrease in that peptide, but then it comes back to normal after a few weeks.

The other thing it might do is it might serve as a capacitance chamber. If the left atrial pressure goes up, if a person is vigorously exercising or let’s say they’re a triathlete or something, there’s some conjecture – there’s no firm evidence but some conjecture that the appendage might serve a purpose in those patients with respect to reservoir function for blood, or somebody who has a left ventricle that’s particularly stiff, maybe it serves as a reservoir function.

Our concern there with eliminating the left atrial appendage in patients with those issues, especially people with diastolic congestive heart failure or left ventricles that don’t work well, that concern has pretty much been allayed in the sense that there was the most recent study looking at closure of the left atrial appendage in people with atrial fibrillation in a randomized control study, the largest of its kind, did not see an increase in heart failure because that was the concern. Would we end up having people develop heart failure because we closed their appendage? We did not see that signal in the largest randomized control study in the history of atrial appendage management – surgical atrial appendage management, I should add.

We’ve got this vestige from our infancy that now doesn’t serve a real powerful purpose, but it does put us at risk, right, so we know that when people are in atrial fibrillation that the appendage serves as a nidus or a place where they will form clot. Why is that happening? It’s happening because the upper chamber instead of squeezing like this is doing this, and during that time, the flow of blood will stagnate. It stagnates most in the left atrial appendage because it’s a pouch, and also, the left atrial appendage because of its fetal origins has a lot of folds on the inside, and those folds act as a place for clot to form. The rest of the atrium has very little in the way of changes in surface architecture. It’s very smooth, so it tends not to get clot on it, but we tend to get clot in the appendage. Stagnant flow and a surface that promotes that clot formation.

Then the question becomes when do you close it? In whom should you close it? This is one of our hottest topics and has been for many years. We have evolved to the understanding that anybody who has atrial fibrillation given the opportunity if they have some risk factors should have the appendage closed, so I already muddied it up. I said some risk factors. There’s a scale. It’s called a CHADS-VASC score. It’s basically looking at congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, vascular disease, and gender to stratify somebody’s risk. If they’re in atrial fibrillation, what is their risk of stroke? We know that for folks in atrial fibrillation, most of the clots that form are in that left atrial appendage, so there’s the correlation between the CHADS-VASC score, the risk stratification, and the appendage.

It doesn’t mean that eliminating the appendage eliminates the risk of stroke. It does not eliminate it. It dramatically reduces it. Then you have to decide what’s the threshold for atrial fibrillation. We know the CHADS-VASC score, and let’s say our patient has a CHADS-VASC score of three. We consider that moderately elevated. Composite score, you get a point for each thing except stroke you get two points, age is 65 and 75, a point for each depending on your age. Let’s say you have a CHADS-VASC score of three. CHADS-VASC score of three is moderately risky. It makes sense to treat the appendage if they’re at risk related to their atrial fibrillation, but now you’ve got somebody who has 3.2% of the time in atrial fibrillation, and there is a continuing debate – it’s been going on for years – about what the threshold is for how much AFib you have to have to be dangerous.

There are two things we know. One is that a lower burden over all is less risk. We also know that the amount of time that a person spends in atrial fibrillation for any given period is what drives the risk as well, so if 3.2% of the time you’re in atrial fibrillation, but it’s thirty seconds, five times a day and that’s your whole – that’s your drill, always the same thing, it’s really hard to have a stroke from that, but if it’s five minutes or six minutes multiple times a day, or if it’s five hours once a month, then you’ve got these risks. That needs to be deciphered. In other words, if a person has the opportunity to look at their continuous recording, which our patient does, then they can look and see what the burden was, when it happened, how long they were in atrial fibrillation. That information will be organized into their package with their risk stratification from the CHADS-VASC score and then determine the appropriateness of treating the appendage.

I would add the Watchman’s a very good device. The Amulet’s a very good device. The devices that they use to close the appendage percutaneously are really boons to mankind in the sense that for folks that we cannot anticoagulate and are left with that structure that is high risk and if they are in the high risk category – let’s say they have a CHADS-VASC score of five and they’re in atrial fibrillation all the time and they have an enlarged left atrium – we’re going to get back to that – those folks really should have their appendage managed, and this gives them a way to do it.

If you look at the original studies that led to the FDA approval for the Watchman device, the Watchman device if you took the composite of the endpoints, which were bleeding and stroke, bleeding and thromboembolic events, it did well. It faired well against Coumadin, Warfarin, the gold standard for preventing clot formation, but if you compared just the stroke risk or the thromboembolic risk – in other words the likelihood of getting a clot and having that clot break off – it was still higher for the Watchman because it’s a foreign body sitting inside of the left atrium, and we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking that’s completely always benign. It’s just not. It’s still better than an open appendage for sure, but in the competition for thromboembolic risk reduction, it didn’t win against Coumadin.

Our patient was on Eliquis. I think is not on Eliquis now, and that happened because after oral surgery, he had a bleed. That’s a one-time event related to a procedure. I, personally, looking at – I’d have to look at the person, all the comorbidities, etcetera, but Eliquis is a really good drug. It’s a really good drug at reducing the risk of stroke, thromboembolic events. It also has the best bleeding profile that we can identify. People can talk about some of the nuances of the studies, but it has a low bleeding risk as an oral anticoagulant.

Indeed, if our patient has periods of AFib that put them at risk, if our patient has perhaps other conditions that concern us for example atrial myopathy, which means an enlarged atrium, an atrium that doesn’t move well, that promotes or lends itself to stagnation of flow, then the appendage should be managed, but there are different combinations. One combination would be going back to full dose Eliquis and making sure that – just seeing if you have another bleed. The second would be putting the Watchman in and then maybe – some people think this is heresy, but maybe in someone who’s low risk, still having them on perhaps a lesser dose of blood thinner. Finally, just putting the Watchman in and then recognizing that now you don’t have to be on blood thinner, but you still have a little bit of risk of thromboembolic event.

If I were the patient, I would want to know all of those things. I would want to really understand my burden. I would want to understand how long the periods of atrial fibrillation are because that is what will determine the risk, and I would want to know the architecture of my atrium, the size of my appendage. Even the size of the appendage is important. There was a big study from Europe looking at the relevance of just appendage size in the likelihood of developing a stroke in the course of one’s life. In a larger appendage, you were more likely to have a stroke.

It probably signaled additional pathology in the atrium, this atrial myopathy I was referring to before, so to get back to that, if we look back in the old data just looking at size of atrium, just the size of the atrium, we know that an enlarged atrium is actually predictive of morbid and mortal events in a person’s life, so a severely enlarged left atrium predicts mortality in men, mortality and stroke in women, and it actually begins in moderate left atrial enlargement and then it starts to ratchet up, so just a bigger atrium.

Someone might say why is that. It’s probably a couple of things. One is it signals comorbid conditions, other things that are happening to the patient’s body and heart. It also signals stagnation of flow, more risk of atrial fibrillation that they cannot detect. This patient has a defibrillator so he’s constantly monitored. If you’re not constantly monitored, you don’t know if you have atrial fibrillation. In fact, if someone comes to the emergency room with a stroke and they’ve never had a history of atrial fibrillation and you monitor the patient, about 20% of them are going to have atrial fibrillation that was not diagnosed before. Is that always the cause of their stroke? Maybe not, but the fact that that atrial fibrillation is there certainly was a risk factor for having the stroke. You can see this blows into this really big conversation.

Then we recognize for someone like this who’s had multiple heart surgeries and depending in the time of someone’s life and what their long game management is, what the strategy is for their valve disease, maybe perhaps some of those patients need their appendage managed early. We’re trying to answer that question. We don’t have an answer for that. I’m not advocating that everybody have their appendage closed when they have heart surgery, but I am saying probably there are some people that should. We have the LAAOS III trial, which I mentioned before. Rich Whitlock, who’s a heart surgeon in Canada, brilliant guy at McMaster University was the point guy for that study.

That brought us to where we are now, which was definitive evidence that whether a patient was – whether patients were on standard care blood thinner or not, if their appendage was surgically closed at the time of heart surgery and they had atrial fibrillation, their risk of stroke was significantly reduced, so this means patients were managed the same way. If you had your appendage closed or not, you were still managed by standard of care anticoagulation – oral anticoagulation. Whatever your doctors prescribed, however they could get it into you, that’s what happened. The patients who had their appendage closed still had a reduction.

Now the question becomes should we be more aware of folks that might eventually develop atrial fibrillation or is the atriopathy itself, the changes in the size and geometry of the atrium, is that enough of a cue for us to go after the left atrial appendage during surgery. As many people know, now we can close an appendage in 30 seconds. We have a clip. We put the clip on, we’re done. We have done those studies. We have documented the efficacy of those devices at better than 98% efficacy with essentially no significant complications, so we have a way to do it that’s safe and fast in the operating room.

Now we’re doing – and I mentioned Rich Whitlock. He’s actually the global PI. I’m one of the national PIs with a few other really fun and bright people, principal investigators, to determine whether closing the appendage prophylactically in people makes sense. If somebody has risk factors, if they have atriopathy – an atrium that doesn’t function normally – if they have the CHADS-VASC score elevation that leads to risk in people who have atrial fibrillation, should we close their appendage prophylactically? We are doing that study now. It’s 6,500 people that will be enrolled. It’s an international study. Our center enrolled the first couple of patients in the study, and now multiple study centers in the US have enrolled. It will be a pivotal and super important study to finally answer this question so that surgeons and patients will be comfortable with the decision making around managing the appendage.

Think about how little the appendage is. Here we are – I have not stopped talking for I don’t know how long – 15 minutes. It’s this little thing that can cause so much trouble and creates so much potential injury for people, and so we have to think about it in terms of whether we should be addressing it whenever we have the opportunity in the patient who’s at risk.

Adam Pick: Wow, wow, and more wow, Dr. Gerdisch. Lee, I really hope that information helps you. Dr. Gerdisch, as a follow-up, you referenced a new clinical trial that you’re working on, but I don’t know if you shared the name with our patients. What might it be so they could do some additional research on it?

Dr. Gerdisch: Sure. We named it LeAPPS, so it’s uppercase L, lower case E, and then A-P-P-S, and it stands for Left Atrial Appendage Exclusion for Prophylactic Stroke Reduction Trial.

Adam Pick: For the patients out there, they can go to clinicaltrials.gov and type in the acronym, and there you can learn all about that study that’s underway. Dr. Gerdisch, on behalf of Lee, on behalf of all the patients at heartvalvesurgery.com, patients all over the world, thanks for taking time away from your very busy practice there at Franciscan Health and sharing all this incredible insight with our community. Thanks for being with us today.

Dr. Gerdisch: My pleasure, and thanks to Lee for an important question.

Adam Pick: Hi, everybody, it’s Adam. I hope you enjoyed that video, and don’t forget you can always subscribe to our YouTube channel. Watch the next two educational videos coming up on your screen or click the blue button to visit heartvalvesurgery.com.